To lose one club may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose two looks like carelessness. Had he been a 21st century rugby aficionado, we can only speculate what Oscar Wilde would have made of the loss of a third in the same season. Reckless irresponsibility? It was only three years ago Wasps, Worcester Warriors and London Irish all went belly-up in swift succession, and it shook the game in England to its foundations.

At the time, serious questions were raised by a parliamentary report about the financial sustainability of a private ownership model in rugby. When negotiations began on the new Professional Game Partnership between Premiership Rugby and the RFU one year later, which meant additional leverage for the union rather than the clubs. As events on a heady summer of major tours unfold, it is rapidly becoming clear player welfare runs hand in hand with governance of the game.

One of the key stipulations of the new PGP agreement was player involvements should be reduced to 30 games per season – and “involvement” meant “any time [at all] spent on the field”. An iceberg of physical and mental preparation belies even an 80th-minute substitution. The research had been undertaken at the University of Bath and funded by the Rugby Players Association, and the study found 31 or more match involvements resulted in a significantly higher injury rate in the following season.

Under the previous 2018 agreement, players had been limited to 35 total games and no more than 30 full, 80-minute appearances, so it was a very significant change indeed, and it was backed up by sanctions for those breaching the new welfare principles. Directors of rugby and/or head coaches now have to accurately predict future involvements in the knockout stages of the league, the Champions Cup and international matches over a 12-month span for their players. They need a crystal ball, some moody lighting, and a colourful caravan as part of their job description.

The tendency in leagues with a private ownership model is to invest a very high proportion of total revenue in player salaries [typically 90%+ in the Premiership] and then get the star names on the field as much as possible. After the last pre-Covid, ‘full metal jacket’ British and Irish Lions tour of New Zealand in 2017 had finished, some fascinating stats linked to the allowances made for player rest and recuperation in the following season were unearthed.

Union-managed players from Ireland enjoyed an average of 83-84 days of R & R before returning to domestic duty in 2017-18, while England players had a wider spread, and far less overall rest, ranging between 55 and 71 days off. The Irish players who contested the 2018 Six Nations averaged 4.5 fewer game involvements than their English opponents on the final weekend of the tournament. Unsurprisingly, Ireland won.

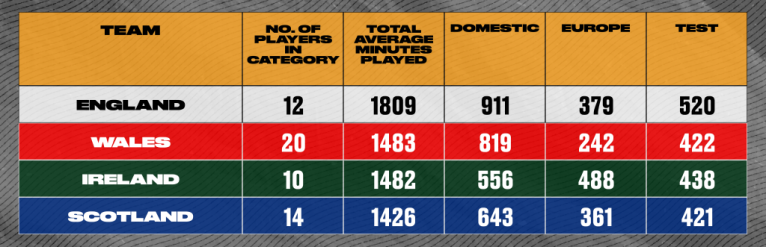

It was the same the following season, Wales achieved a Six Nations Grand Slam and victory in a climactic game in Cardiff over Eddie Jones’ England. An article on The Blitz Defence presented a compelling comparison of the of the exposure of the top players [awarded between seven to nine caps] in the home unions.

Ireland, Scotland and Wales all ply their trade in the URC [then the Pro 14], and in Ireland and Scotland the top players are typically contracted to the union, which manages player welfare issues and the wage structure which supports them. At the time, Wales were still labouring in the throes of a dying private ownership model, but the domestic demands on its players were relieved by the relative lack playing time in European competition.

Wind the clock forward to the last two tours of New Zealand which preceded France’s current visit – by Ireland in 2022 and England in 2024 – and it is very much an echo of the same song.

In my previous article on the France tour of New Zealand, the insurmountable difficulties of the French selection process became clear. Fabien Galthié was stuck between a rock and hard place. If the French supremo had picked his ‘A’ team from the final Six Nations game against Scotland, 91% of the players would have surpassed either one of his two player welfare criteria [2,000 minutes and/or 25 games]; as it was, the ‘B’ team who pitched up at the Forsyth-Barr Stadium for the first Test still contained 74% of players who broke the rules.

Unlike France, England decided to pick the bulk of their Six Nations team to tour New Zealand in 2024, even though only six of the chosen players in a typical Test-match 23 fell comfortably within the French welfare criteria. There were seven [in red] who shattered the 2000 minute and 30-plus game barrier, and another five who were close to the red line [in pink].

A 10-match Lions tour will only magnify the holes in the welfare system, and the usual suspects all ply their trade in the Premiership. Prior to Saturday’s first Test victory, captain Maro Itoje had played 2297 minutes and 30 games, Finn Russell had 2513 minutes and 34 games, Tommy Freeman had 2362 minutes and 31 games, and Marcus Smith was up to 2219 minutes and games.

A very different picture emerged from Ireland’s history-making tour of New Zealand in 2022.

Not one player in that group exceeded either of the French thresholds for player welfare before the Test series started. Where England came agonisingly close to success by retreading a fatigued ‘A’ team in 2024, and France abandoned all hope of winning the Test series ahead of time by picking a ‘B’ squad one year later, Ireland were able to manage their resources far more efficiently. The visitors won the 2022 series by tapering to a peak in the final two Tests, mirroring the success of the fabled 1937 Springbok tourists.

The difference between Ireland on the one hand, and England and France on the other, is the player welfare equation is managed by the union in close concert with their four URC provinces. In practice, there is one entity with a single aim responsible for linking playing exposure at club and international level. In France there is the FFR and the LNR, in England there is Premiership Rugby and the RFU, and with two comes a slight but inevitable splintering of purpose.

Within the private ownership model, France’s Top 14 has proven to be an outrageous success while England’s Premiership has yet to prove its sustainability. Put simply, in France rugby is more popular than soccer, but in England that will never be the case. The current TV deal for the Premiership sits at 45m Euros per season but Canal+ pays nearly 130m for the dual rights to televise Top 14 and Pro D2. Ticket sales in France broke previous records at 5.5m across the two leagues in 2023-24, but gate and broadcasting revenue still only accounts for 35% of total income, with ‘partnerships’ [sponsors and wealthy benefactors] still the major source at a whopping 44%.

Whether it is winning or losing, the private ownership model still has a problem with the [over-] use of its primary assets, the players. Most of top 50 players in the country cannot meet France’s own professed player welfare criteria for the tour of New Zealand, and many of the top Premiership stars are already breaching the recommendations made by the University of Bath before the Test series against Australia ever began. Even the well-managed core group of Leinster players will be tested to the limit Down Under.

Strangely, the next litmus test may come in that new rugby backwater, Wales. The WRU is now contemplating the regional solution it should have considered 22 years ago: two teams, East and West Wales ‘which can compete’ at the very pinnacle of the club game.

Two of the existing four regions [Ospreys and Scarlets] are under private ownership, one is owned by the union [Cardiff] and the fourth was sold back to a private consortium by the WRU only two years ago [Dragons]. If four are melted down and two moulded in the crucible, there will be an opportunity for increased union involvement in player welfare, and for a unified wage structure to be created; in the bigger picture, for the sport of rugby to adapt to a new reality. Why keep pressing the button on the remote control when the battery is dead?

Yep they cannot those four top backs playing to exhaustion again next season if they want to ‘do the double’!

The huge squad depth is largely due to the academy and for UBB it's coming. A lot of U20 national team is coming from Bordeaux.